Dr Leonora Long, a science writer at Neuroscience Research Australia, recently took an interesting look at my Membrane Art:

As part of the 2014 SALA Festival of South Australian Living Artists, the RiAus FutureSpace Gallery is proud to present Under the Surface. Using different artistic forms and media, Malcolm Koch joins Christopher and Therese Williams in an exploration of what lies beneath the surface of the world around us. This exhibition will run from August to September.

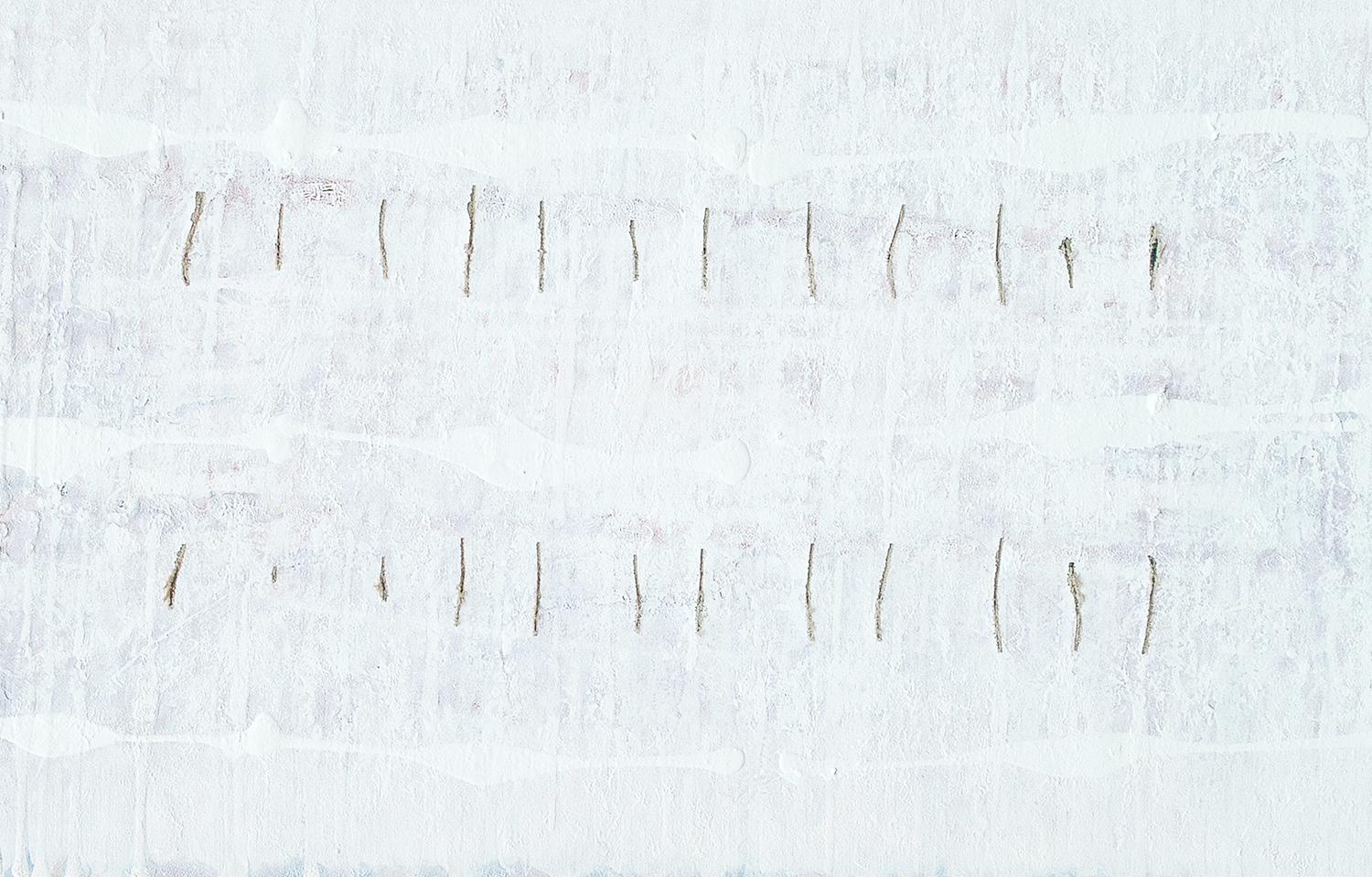

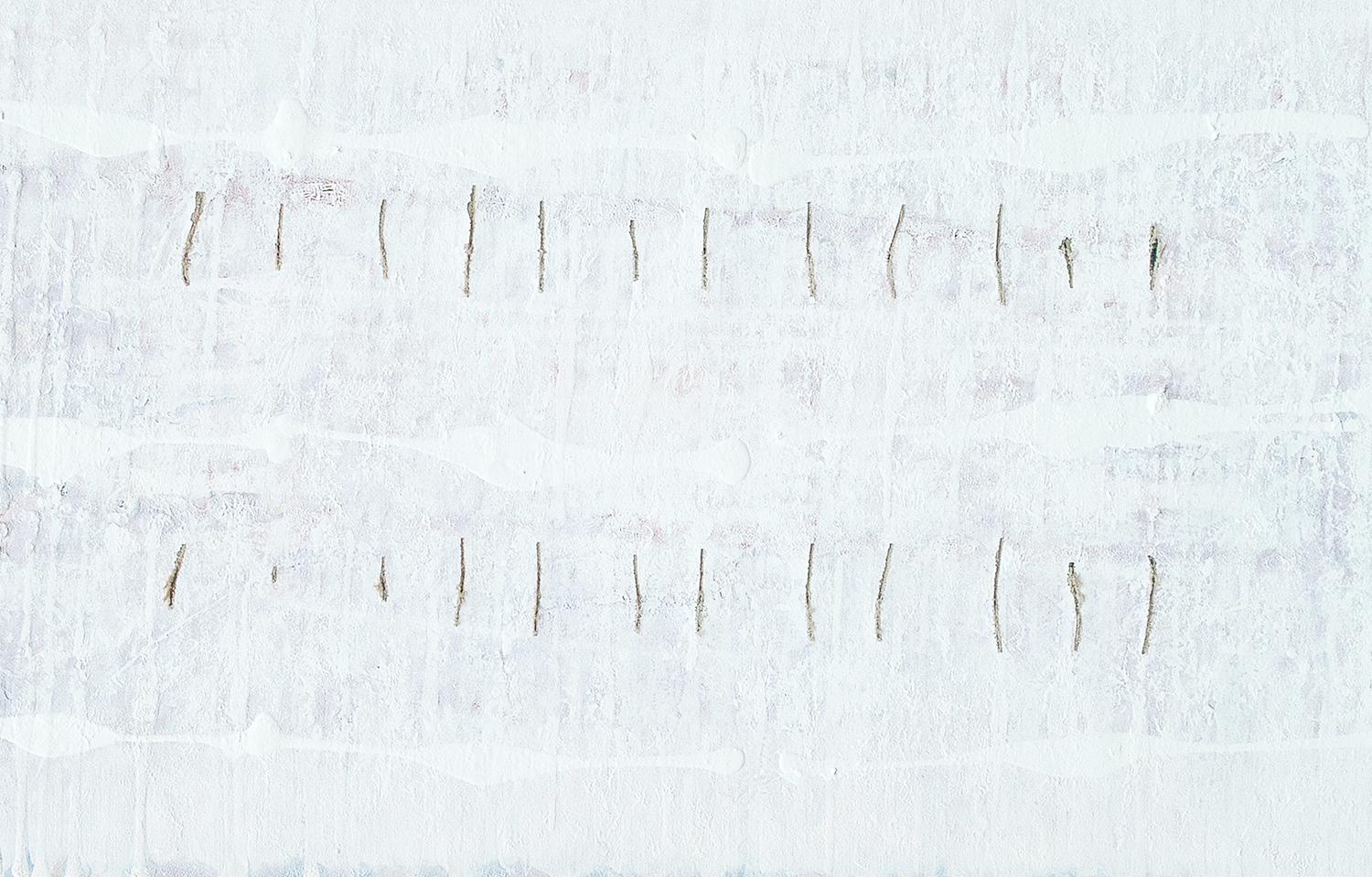

The theme of the 2014 RiAus SALA Exhibition is ‘Under the Surface’. This might bring to mind the earth’s surface – perhaps appropriately, given that one of the exhibited artworks will be Christopher Williams’ soundscape, and Therese Williams’ visual interpretation of that soundscape, captured from the surface of salty, acidic, mostly dry Lake Tyrrell. The work of another SALA artist, Malcolm Koch, is reminiscent of biological entities like membranes and folded organs. Strong contrasts are central to Malcolm’s manifesto of Membrane Art: undulation as a representation of the internal workings of nature and, conversely, the flat plane as a medium for human observation. Let’s take Malcolm’s suggestion to ‘open out the membrane’ and look at the secrets beyond one of biology’s most interesting curled and rippled interfaces, the brain.

The human brain consists of around 86 billion nerve cells, or neurons, and about the same number of non-neuronal cells. Its outer layer, the cortex, is folded into sulci (furrows) and gyri (ridges). These cortical undulations allowed a large surface area to develop in the relatively small space inside the skull. Most of the folding of the cortex occurs in the third trimester of gestation and the first two years of postnatal life, peaking at around age 5 or 6. This rapid increase in folding corresponds with the growth and branching of the ends of neurons, increasing the possibilities for new synapses between neurons to be formed.

MA#47, oil on Belgian linen, 2014. On display at RiAus FutureSpace Gallery until 26 September, 2014. Above: 12 individual cuts of a circular-saw on the undulating (folded) surface, have materialised as 24 cuts when opened out. This hints at particle physics, where it’s possible to be in several locations at the same time. Its only when we observe the cuts on the flat 2D surface do we realise that there’s a relationship between two particular opposite cuts that couldn’t have possibly have occurred unless the surface was in a different state. A metaphor for the way we observe.

MA#47, oil on Belgian linen, 2014. On display at RiAus FutureSpace Gallery until 26 September, 2014. Above: 12 individual cuts of a circular-saw on the undulating (folded) surface, have materialised as 24 cuts when opened out. This hints at particle physics, where it’s possible to be in several locations at the same time. Its only when we observe the cuts on the flat 2D surface do we realise that there’s a relationship between two particular opposite cuts that couldn’t have possibly have occurred unless the surface was in a different state. A metaphor for the way we observe.

Given that the synapse is the basic communication unit of the brain, it makes sense that they need to grow a lot in early life. Think about how different from one another are a newborn, a six-month-old baby, and a two-year-old toddler. Smiling, eating, sitting, sleeping, walking and talking all require a lot of growth and development! Not all animals have the same degree of gyrencephaly, or cortical folding. For example, the mouse cortex is quite smooth. While it also has 1000 times fewer neurons than the human, it seems that the total number of neurons is not the key difference between mouse and human cognition. The surface area of the cortex (increased by all that folding) is increasingly seen as central to the increased cognitive ability in humans.

As we zoom in on individual neurons we can see more examples of the importance of folding and membranes. At this level there are many more similarities between animal species than differences. For example, all neurons are surrounded by a membrane, as are the structures inside the neurons. The membrane is made up of molecules called phospholipids, which arrange themselves in a bilayer, and this structure helps to determine the permeability of the membrane, or what molecules can pass in or out of the cell. This permeability changes depending on the electric charge on the membrane surface, or by a change in shape of one of the proteins that stud the membrane like embedded jewels.

Some proteins act like channels and extend all the way through the membrane, and in response to an outside stimulus, these channels open up and allow a stream of charged particles to pour into the cell. This flow can dramatically change what happens in the cell. It might be the signal for the cell to release a neurotransmitter, or it might switch on a gene that regulates neuron growth.

What might at first glance seem like a static barrier between a cell and its environment is, in reality, constantly moving like long grass in a breeze, with molecules passing through it as part of the cell’s functions. It is the individual nature of the genes, proteins and other molecules in a neuron that give rise to the structural and functional differences between species.

As we zoom in even further we can reveal a world of folded proteins and molecules that conceal even more secrets that determine the way cells function, independently and collaboratively. We will continue to find folds within folds that all play a part in the eventual activity of our brains.

We can’t always see what is happening beneath the surface in real time with our unaided eyes, and so as far as neuroscience is concerned, we may not be able to wrap our brains around the ‘absolute idea’ spoken of by Malcolm Koch, but at least we have built these increasingly objective measurement tools to be our surrogate observers.

By building scientific observations into new knowledge, new hypotheses can be made and tested and results can be interpreted to derive new meanings. In this process, the truth itself doesn’t change. Its nature just becomes clearer to the observer. Perhaps the idea of compressing the depth of an undulated surface into a flat plane is symbolic of science’s aim to grapple with the complexities of the world: not to simplify them, but to aid their experience from many subjective viewpoints.

By Leonora Long (@leonoralong)

Article courtesy of Royal Institution of Australia: RiAus – Australia’s Science Channel

Science meets Art: Nature becomes clearer to the observer when you compress the depth